West Coast fishing communities range from tiny unincorporated hamlets to urban metropolises like San Francisco and Los Angeles. They include tribal communities where fishing has been occurring for millennia.

On a technical level, the term “fishing community” can refer geographically to a place where fishermen and women live (Newport, Los Angeles, Neah Bay), or more abstractly to a community based on gear type, fishery, geography, values, or other factors. For example, an “occupational community” is a group of people involved in the same occupation, like the coastwide community of recreational anglers. A “community of interest” is made up of people who share similar interests: for example, people who are concerned about reducing barotrauma in rockfish. One town or city might include many different occupational communities and communities of interest.

But what is a fishing community, really?

Social scientists spend a lot of time defining “community” so that fishing communities can be studied and compared. The Magnuson-Stevens Act (MSA) defines a fishing community as ” …a community which is substantially dependent on or substantially engaged in the harvest or processing of fishery resources to meet social and economic needs, and includes fishing vessel owners, operators, and crew and United States fish processors that are based in such community.” In interpreting this definition, National Marine Fisheries Service has stated that “A fishing community is a social or economic group whose members reside in a specific location.” This “official” interpretation means that a fishing community exists in a specific place.

However you define fishing communities, it can be said that they are composed of diverse, independent people who do not fit easily into neat categories and who rarely, if ever, present themselves as a homogeneous group.

The community conundrum

Most funding for fisheries management goes towards biological research and management, not studies of fishing communities. In addition, the instability and complexity of the fishing industry make it very hard to pin down. Census data does not differentiate between fishery and forestry occupations, and concerns about identifying individuals, businesses, and privileged information limits the publication of useful economic data. To complicate matters, many fishing communities are unincorporated or are parts of larger communities that do not rely on fishing (for example, Los Angeles). Also, many fishing community members only fish part time, or hold other jobs while they fish. In a way, collecting community information is about as hard as collecting information on fish stocks: both populations are highly mobile and exist in a complex and constantly-changing universe.

What does the law say about fishing communities?

The 1996 revision of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act, which is the basis for fisheries management in the United States, recognizes the importance of human communities and their relationship to fisheries. Among other things, its National Standard 8 declares that fishery conservation must take into account the importance of fishery resources to fishing communities, with the goals of providing for the “sustained participation” of those communities in fisheries and minimizing “adverse economic impacts” as much as possible. This focus on communities represents a subtle shift taking place in many areas of natural resource management. However, funding for studying the effects of management on communities remains at a low level.

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process also calls for an assessment of the impacts of actions on communities. As part of the NEPA process, both economic factors (economic base, employment, revenue, income, etc.) and social factors (population dynamics, social institutions, environmental justice, cultural values, community identity, history, etc.) need to be addressed in environmental assessments and environmental impact statements. However, NEPA states that “economic or social effects are not intended by themselves to require preparation of an environmental impact statement.”

In addition to these Federal mandates, a growing number of natural resource managers recognize the importance of including the views and values of diverse stakeholders, including fishing community members, in the management process. In fact, the Council process was set up specifically to include stakeholders in the process. People who effectively represent the concerns of their communities can help create more effective and efficient fisheries management.

What research and data collection is taking place?

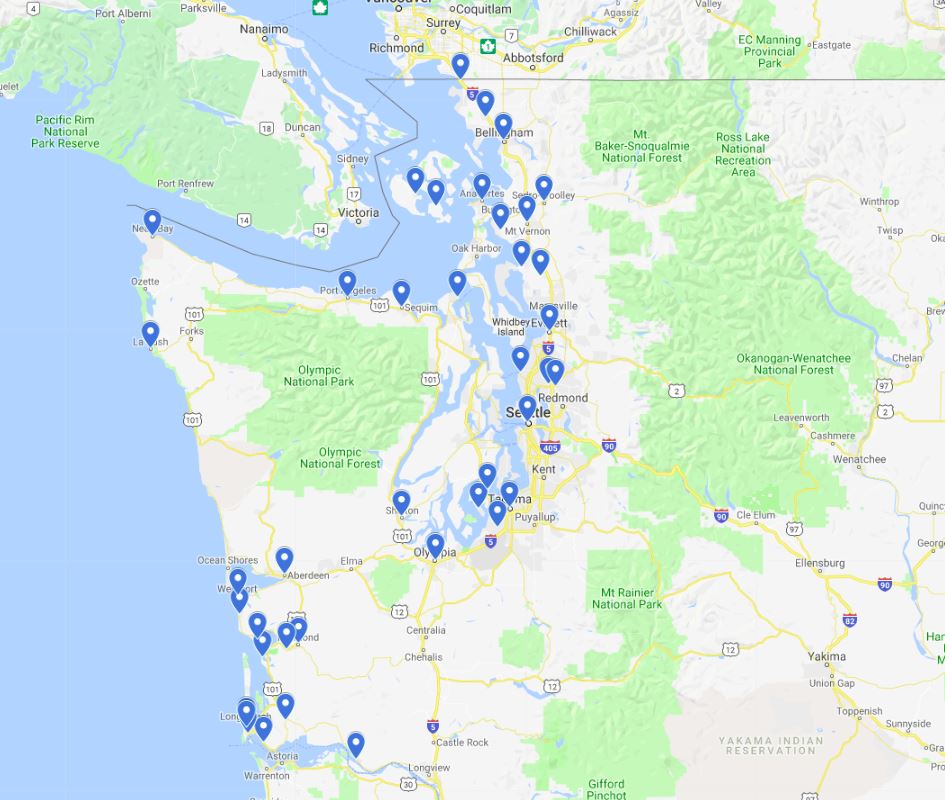

- NMFS anthropologists and economists at the Northwest Fisheries Science Center have developed community profiles for West Coast fishing communities. These summaries are used in environmental impact statements and management decisions.

- Council staff have developed a white paper on non-economic social science in the Council process. The Council’s Research and Data Needs document outlines the Council’s needs in these areas. It is updated on a biennial basis.

- The Fisheries Economics Data Program (EFIN) conducts annual industry cost and effort surveys. It has also collected several datasets of interest to fisheries economists, including labor and wage statistics, fuel prices, and measures of changing prices and living conditions. EFIN is housed at the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission.

Other resources and publications

- Oregon Sea Grant, Washington Sea Grant and California Sea Grant sponsor research on economic and community development

- NOAA Office of Science and Technology: Human Dimensions

- Fishfolk, a fisheries social science discussion group